Reading time: 6 minutes / Lars Buchwald / 08/08/2025

The Art of Opening

Contents of the Article

→ Why we pick locks in the first place

→ The roots: Yale, Bramah & the man who cracked the uncrackable

→ Lockpicks go industrial – welcome to the post-war era

→ Snap guns, patents and a quantum physicist with too much free time

→ Lockpicking 2.0 – smarter, faster, more connected

→ When sport meets security cylinders – the Dutch Open

→ And tomorrow? Locks that talk – and might even think?

Over the past hundred years, the art of opening has evolved from simple wire bending to high-tech lock picks – a pretty good reflection of our technical progress and the growing desire for more security (or at least clever ways around it). What we now know as modern opening techniques would be unthinkable without countless trials, failed experiments, and the almost stoic persistence of those who came before us.

Why do we do what we do?

Sometimes it's quite simple: a problem arises – so someone has to solve it. That’s probably what Alfred Hobbs thought too, the man who would later cause a small revolution at the Great Exhibition in London in 1851. Today, many years later, we see it as our duty to carry Hobbs’ spirit forward and tackle the modern challenges of our century. No less exciting than back then, but with very different possibilities. So let’s begin with a look into the past – and, of course, a glimpse into the future.

The Beginning & Industrialisation (up to around 1950)

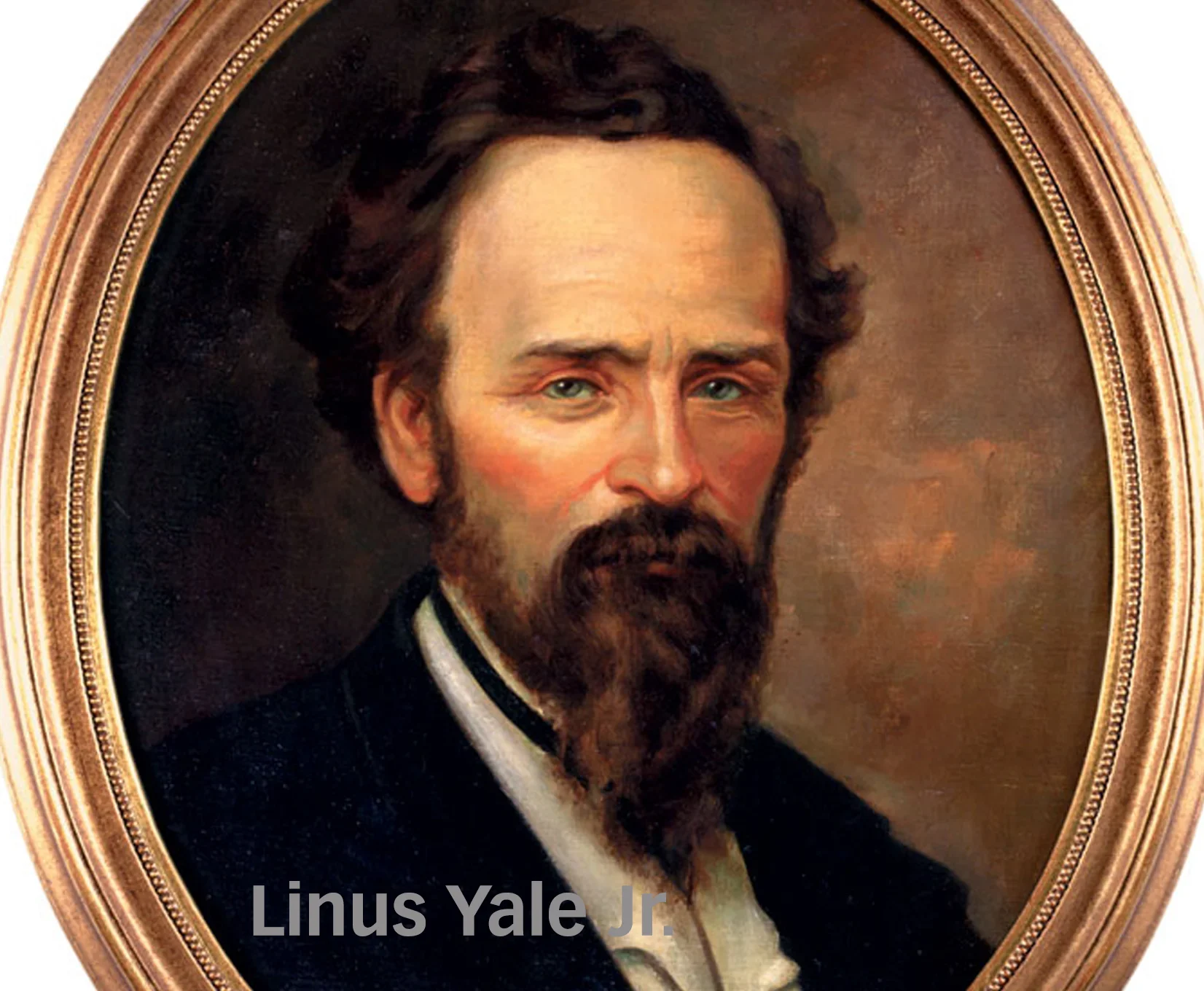

Linus Yale Jr. – The man who gave us the cylinder lock

Born in 1821 in the state of New York, Yale Jr. was something like the Steve Jobs of lock pioneers – only with metal, and a bit less marketing. His father, Linus Yale Sr., was already a passionate lockmaker. But Yale Jr. thought to himself: “It can be made even more secure.” And so, in 1861, he invented a lock that still accompanies us today – the pin tumbler lock.

The invention found in (almost) every door

What made it so special? Tiny pins that would only align correctly inside the housing when the right key – with the exact matching cuts – was inserted. Suddenly, the key was flat and practical in design. A shape that has hardly changed to this day. And if you’re holding a cylinder lock now – whether made by Yale or any other manufacturer – it’s still built on the same concept he envisioned and realised back then. Some things are simply hard to improve.

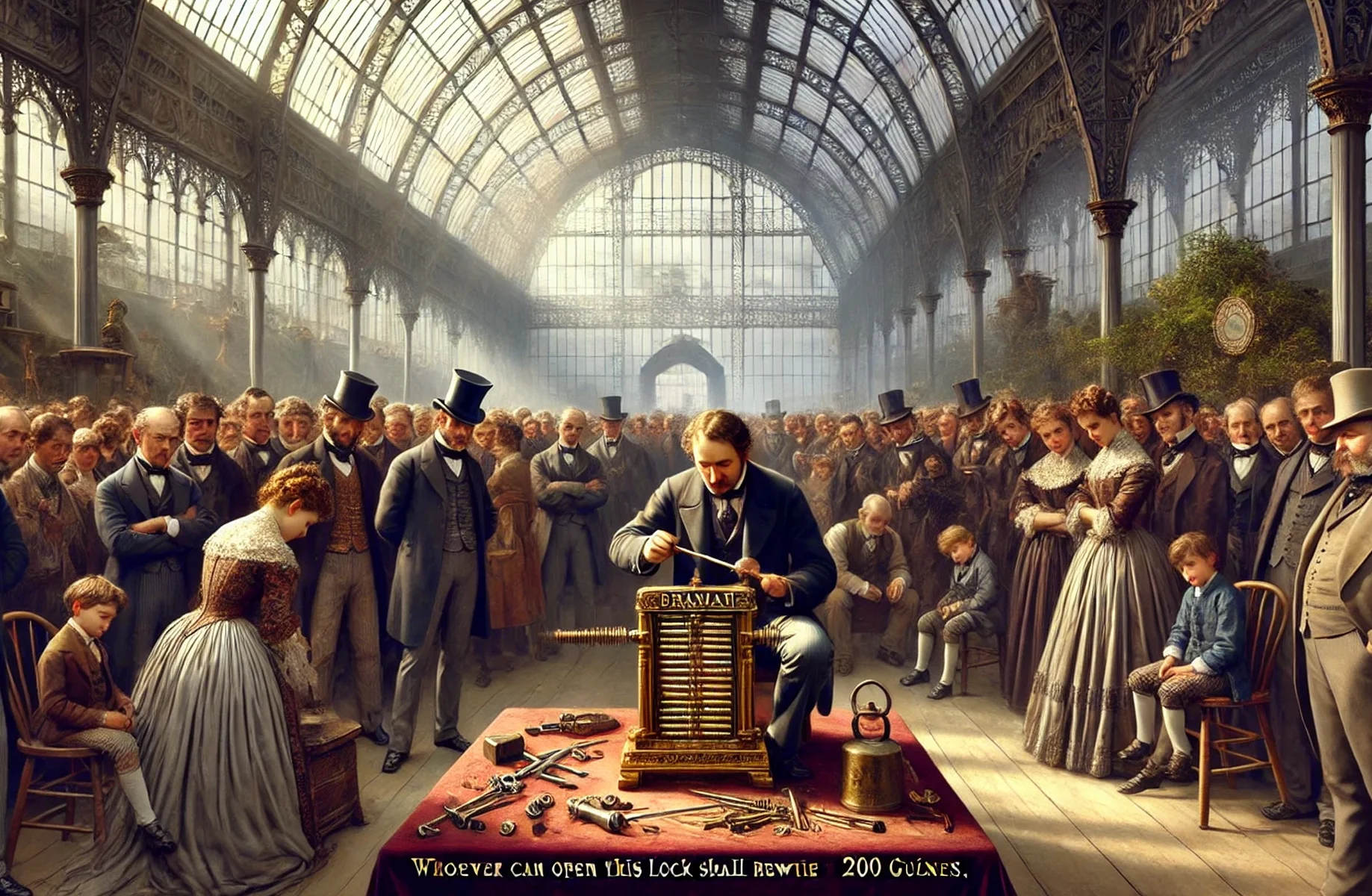

Many years before Yale, another man designed a lock that would become legendary: Joseph Bramah, and his “Bramah lock – a lock for the ages”.

Born on 13 April 1748 in Yorkshire, England, he was an inventor, engineer, and mechanic. Joseph Bramah spent around six years developing his famous high-security lock before patenting it in 1784. A high-security lock with a cylindrical key and rotating sliders inside – more than 18 moving parts in an incredibly compact space. For the time (and frankly, even by today’s standards), it was a masterstroke of engineering.

He was so confident in his creation that he put up a sign in his London shop:

“Whoever can open this lock shall receive 200 guineas.”

That was equivalent to several years’ wages for an average worker – a bold challenge indeed. And what happened? For nearly 70 years, no one succeeded. It wasn’t until 1851, during the legendary Great Exhibition at London’s Crystal Palace, that the American lockpicker and security engineer Alfred Charles Hobbs managed to open the supposedly “unpickable” Bramah lock – a lock that had withstood all attempts for 67 years. Hobbs spent a total of 51 hours over 16 days working on it, under tightly controlled conditions and using purely mechanical methods.

Despite his success, Hobbs later expressed deep respect for Bramah’s work. In his own words, he called the lock “a remarkable mechanical achievement”, far ahead of its time. But his demonstration had far-reaching consequences:

“The notion of absolute security is a fallacy.” – A.C. Hobbs, Locks and Safes (1853)

With this sentence, Hobbs not only ushered in a new era but fundamentally changed how people thought about security. Manufacturers worldwide began focusing not just on protection, but on defining resistance time – asking the key question: How long can a lock withstand an attack? Thus, Hobbs’ cracking of the Bramah lock marked the beginning of modern security technology – moving away from the myth of the unpickable lock toward a realistic assessment of risk. A mindset that still forms the backbone of professional lock design today.

Mechanics Meet Electronics (1950–1990)

From the 1950s: Lockpicks become industrial products

In the post-war era, more precisely from the 1950s onwards, lockpicking evolved from a domain of individual tinkerers into a serious craft with professional ambition. Pick sets, previously improvised from watchmaker’s steel, fret saw blades or guitar strings, were now manufactured industrially – for the first time standardised, durable, and ready to use straight out of the box. Spring steel became the new gold standard: robust, elastic, and perfectly suited for repeated pressure in narrow keyways. This technical progress also reshaped professional practices: locksmiths, authorities and emergency services increasingly adopted pick tools as part of their regular equipment – complete with training and manuals. Lockpicking became more legitimate – and, above all, more mechanical.

The snap gun patent shock – when seconds suddenly became enough

As early as the 1930s and 1940s, the first patents for so-called "snap guns" – also known as pick guns – began to appear. Their principle: a rapid impulse (mechanical, or nowadays electric) causes a striker to hit the pick, which in turn makes the pins in the lock “snap” upwards. With a bit of luck (and skill), the cylinder rotates straight away – click, door open. What used to take minutes – or even much longer – could now be done in seconds. For police, fire services and security forces, a real gamechanger. The earliest US patents for this technique include one by Herman G. Frank (Patent No. 2,020,925, 1935), later refined for tactical use.

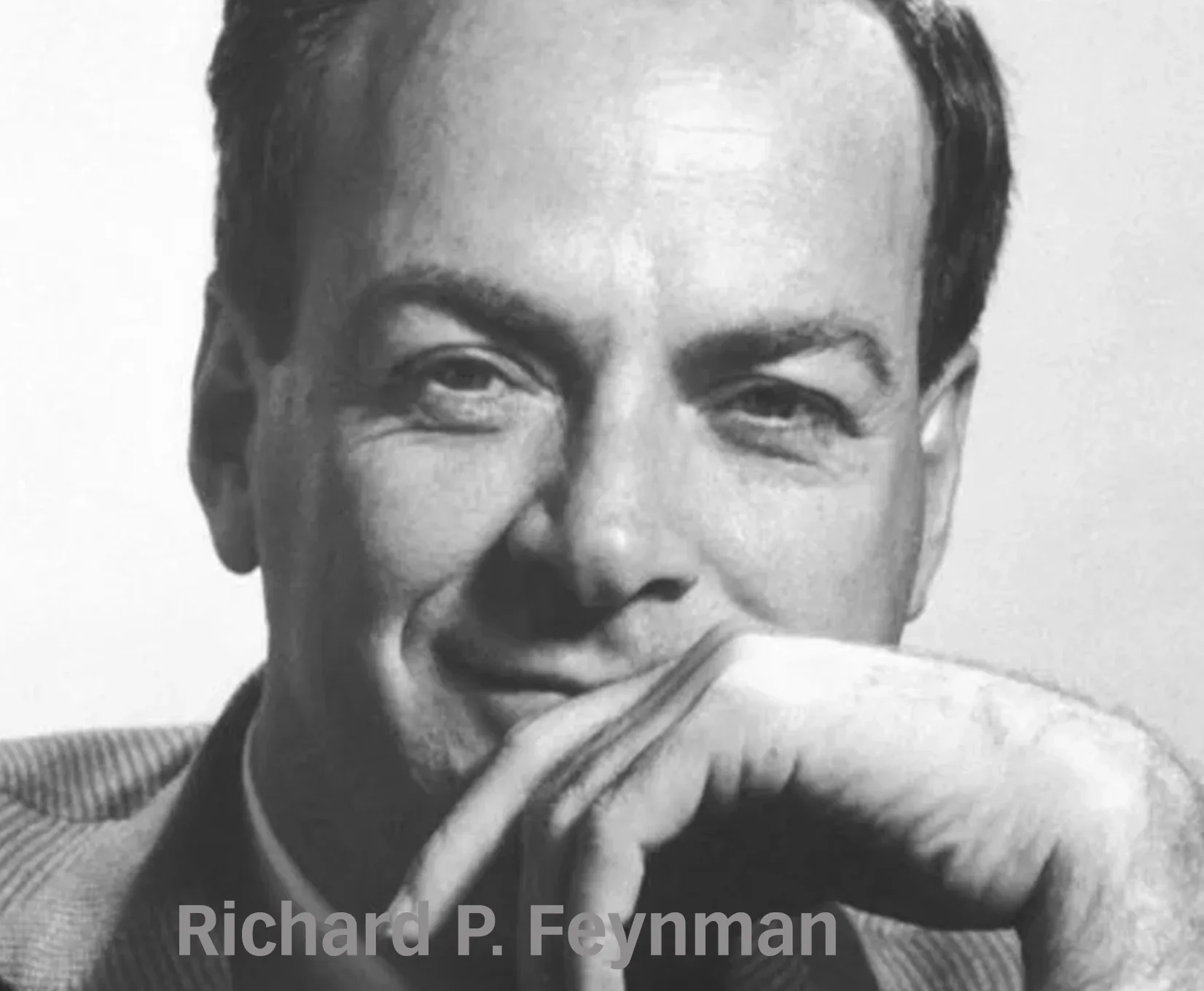

Nobel laureate Richard Feynman – when the man behind the Manhattan Project got bored

And then there was Richard Feynman. Physicist, quantum icon, Nobel Prize winner – and one of the minds behind the Manhattan Project. In his free time – while others played cards or chess – Feynman picked locks. As he later said, “out of childlike curiosity.” He analysed combination locks through logical deduction, tested office safes for weaknesses – and explained with charm and wit how mechanical thinking works. It’s said that Feynman once left a note inside General Groves’ locked safe – Groves being the military director of the entire project. The note read, roughly:

“This lock is not as secure as you think.”

The note caused quite a stir among the security staff – and a wide grin from Feynman. “I never stole anything. I just wanted to understand how it worked.” – Richard Feynman, Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!

If you like, Feynman was the first DIY hacker.

High-tech, Hands-on and Hard Duels:

Lockpicking in the New Millennium (2000 – Today)

From the 2000s onwards, lockpicking took on a whole new look – in more ways than one: technologically upgraded and socially connected. What was once confined to backroom workshops or locksmith kits became stage, sport and laboratory all at once.

Lockpicking 2.0 – modern tools, smarter access

High-tech decoders, computer-assisted safe-opening tools, electric picks, 3D-printed picks – suddenly, lockpicking was no longer just hands-on, but also a matter for CAD software.

From hobby to arena:

Locksport becomes a competition And then came the community – with forums, workshops, conventions and tournaments. The most notorious meeting ground? The legendary Dutch Open, organised by TOOOL (The Open Organisation Of Lockpickers). A place that regularly gives high-security cylinder manufacturers sleepless nights – because here, the best of the best from the global lockpicking scene go head to head.

A legendary moment for all lockpicking enthusiasts

During one Dutch Open tournament, German competitor “Arthurmeister” picked a six-pin high-security cylinder in just 20 seconds – live and under competitive conditions. A video of the session made the rounds in the community for a while and was jokingly dubbed the “final boss moment”.

And where do we go from here?

The question is no longer whether lockpicking will evolve – but just how weird it’s allowed to get.

So what will the locks of the future look like? AI, NFC or fingerprint? Locks are getting smarter. And, well... stranger. We already have systems that open via fingerprint, NFC chip or app. Some can even be unlocked with facial recognition or a “please open” voice command – as long as Alexa isn’t updating again. But in the end, there’s still a cylinder in the door. So is it business as usual? Definitely not – even if we can’t quite say what things will look like in fifty or a hundred years. Maybe the lock of the future won’t be a lock at all, but a blockchain-connected access node with biometric fallback. Or a quantum lock – one that’s both locked and unlocked at the same time, depending on whether you’re observing it. We’ll see – and I’m sure we at Multipick will come up with a solution for that too.

What was once a fringe topic is now a precision sport, a high-tech playground and a social platform. Whether it’s the Dutch Open, LockCon or your local hackspace – lockpicking is long past just opening locks. It’s a means to an end – and a brilliant sport. I, for one, look forward to the coming years and all the challenges they may bring.

Or, as Feynman might have said:

“I’m not trying to break in. I just want to understand how it works.”

FAQ – Everything You Need to Know.

Why should I care about the history of lockpicking?

A deeper understanding of its origins helps you better contextualise modern techniques – whether you're a professional, hobbyist, or security expert. The history of technology isn’t just academic; it’s the foundation for innovation.

How does historical lock design influence today’s security standards?

The ideas of early inventors like Bramah and Yale still shape the way we think about security today – for example, by focusing on “resistance time” rather than “unpickability”. This shift also affects how products are developed and tested.

What does security really mean in the 21st century?

Security is no longer a fixed state, but a constantly evolving concept. While the goal used to be making locks unpickable, today it’s about realistic assessments, intelligent systems, and responsible handling of vulnerabilities. Lockpicking helps identify those weaknesses – before others do.

What does lockpicking have to do with science or technical understanding?

Quite a lot! Lockpicking sharpens logical thinking, precision and the handling of complex mechanics. Richard Feynman even used it as a mental exercise. For tech enthusiasts, it’s a tangible form of applied physics.

How have lockpicking tools evolved over time?

From bent wire to industrial pick sets, from pick guns to computerised decoders – tools have become more precise, durable and specialised. Today, there are tools for virtually every application.

Why is lockpicking also practised as a sport today?

Because it’s not (just) about opening locks, but about skill, strategy and community. Locksport competitions like the Dutch Open show the level of expertise involved – and how fascinating the topic is for many people.

How responsibly are opening techniques used?

Very responsibly – at least when handled correctly. Lock opening techniques are not toys. That’s why we at Multipick focus on clear education, defined user groups and high-quality tools developed for professional use.

What can users learn from the development of these tools?

For example: there’s no such thing as absolute security – but well-designed, high-quality solutions make a real difference. And: those who understand vulnerabilities can better protect themselves – at work or at home.

What role does lockpicking play in training and research?

In many technical fields (security technology, forensics, fire services etc.), lockpicking is part of the training – not for manipulation, but for understanding. And in makerspaces or hacklabs, it’s a creative learning environment.

What does Multipick have to do with all of this?

We see ourselves as part of this development. Our tools, training programmes and innovations are built on over 200 years of accumulated knowledge – bringing it into the present and future. With respect for the history of the craft and a clear vision ahead.

About the Author

Lars Buchwald has been an integral part of the Multipick team since 2006, where he dedicates his passion and expertise to marketing and graphics. As a trained graphic designer and copywriter, he brings a wealth of experience and creativity to his work, which enables him to convey the messages of the ingenious tools in an appealing and convincing way. With a keen sense for the needs of the target group, he steers Multipick's marketing fortunes. His commitment is characterized by a high degree of sensitivity and the right richer at the right time.

As a native of Bonn, Lars not only has close ties to the region, but has also firmly integrated his passion for marketing spear tools into his professional work. His attachment to the city is reflected in his work and gives his marketing campaigns an authentic, Bonn touch.

Related Articles

About Multipick

Multipick was established here in Bonn in 1997 and has had its headquarters and production facilities here on the Rhine ever since.

Why should we leave here? Anyone who has been here before will agree that it is a very beautiful place and that the people are ‘typically Rhineland’, open-minded and friendly. From an early stage, we began to occupy ourselves with a wide variety of entry tools. We tried out lock snappers and core extractors such as the Bell and gathered a wealth of experience with a wide variety of tools. Whether it was a lock pick set or special tools for fire brigades and locksmiths, in the end the door or window had to be opened. In line with the motto, you got the problem and we got the solution.

Many tools, irrespective of hobby or professional, are dispatched from our warehouse to destinations throughout the world.

Opening tool kits for caretakers and locksmiths, pick sets and lock picking accessories for Locksport enthusiasts and Hobbs hooks for specialists to unlock locked safes. There are thousands of different ways to deploy our specialised tools. Our TFG latch plates and key turners allow a closed door to be reopened. QA Pro 2 and our V-Pro core pulling screws can be used to open a locked door. We also offer milling burrs and drill bits for those situations where there really is no other way. Many useful aids such as MICA opening cards, wedges, door latch spatulas, door handle catches and spiral openers, which are all useful tools to help you get the job done. But even if things get a bit complicated, you are in good hands with us. Products such as the Kronos and Artemis electric picks are our top highlights. Anyone who likes to open dimple locks or disc locks will be delighted with the ARES system. For opening windows, we offer you a range of top products from Kipp-Blitz. Favoured by emergency services such as the fire brigade, THW (Federal Agency for Technical Relief) and police. Many of our tools are manufactured in-house. This gives us the liberty to manufacture quickly and in a customer-orientated manner. No lengthy supply chains and subcontractor dependencies. This has a number of advantages both for you and, of course, for our environment. One big advantage is that you get everything from a single source, enabling us to offer you consistent quality. This is also our promise to you, all from a single source, Made in Germany, Made in Bonn - promised.